The recent SEC fraud charges against Longfin Corp (LFIN) are a good opportunity to take a broader look at the grossly misnamed “JOBS Act”, which substantially lowered listing standards while expanding the ability to target less sophisticated investors with risky securities.

(Reminder: I am not an attorney and I do not provide legal advice. The information presented below is my interpretation and opinion based on the facts and links included. If you need legal advice you should consult with an attorney.)

Through its beginning, middle and end, Longfin can be viewed as the poster child for much of what is wrong with the JOBS Act. Longfin Corp (LFIN) was a Reg A+ IPO which raised $50 million at a price of $5.00 per share in December 2017. Within just weeks of that IPO, the share price had spiked to as high as $142 (intraday) mostly due to the company purchasing two somewhat questionable companies directly from its own CEO. Following this 2,700% price spike, Longfin was now worth (on paper) roughly $7 billion based on an investment thesis that could be roughly summarized as “something, something, something, crypto, something.” But within just a few months of its IPO, Longfin was already under SEC investigation for a host of potential violations. In June 2019, Longfin and its CEO were formally charged with fraud by the SEC and its shares now trade for just pennies on the pink sheets.

-

Longfin Corp. Celebrated its IPO on Nasdaq (Globenewswire, Dec 2017)

-

The Curious Case Of Longfin Illustrates The Scale Of Cryptocurrency Mania (Forbes.com, Dec 2017)

-

SEC Adds Fraud Charges Against Purported Cryptocurrency Company Longfin, CEO, and Consultant (SEC.gov, Jun 2019)

The JOBS Act is significantly worse than many people already realize. The Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act was passed in 2012, following the global financial crisis that unfolded during 2008-2009. But despite its catchy name, the JOBS Act did effectively nothing to create “jobs” for Main Street. And in fact it was also a significant negative for those who invest their money via Wall Street. Although it has consistently received criticism in the press, it is still the case that most investors fail to fully comprehend just how problematic the Act continues to be and just how far the problems extend.

- President Obama To Sign Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act (The White House, Apr 2012)

- Spotlight on Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act (SEC.gov)

- Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act (US Congress, Apr 2012)

“The bucket-shop and penny-stock fraud re-authorization act of 2012” . With the US still trying to recover from the worst financial crisis since the depression, there was little risk in 2012 that members of Congress might vote against anything calling itself “The JOBS Act”. But the absurdity of this legislation was readily apparent from the very beginning. Former chairman of the SEC Arthur Levitt put it quite simply, saying: “the bill is a disgrace.” In 2012, the SEC’s former chief accountant said of the JOBS Act that:

“It won’t create jobs, but it will simplify fraud…This would be better known as the bucket-shop and penny-stock fraud reauthorization act of 2012.”

-

Introducing the JOBS Act – or the “Boiler Room Legalization Act” (Nonprofit Quarterly, Mar 2012)

-

JOBS Act Will Open Door to Investment Scams (Forbes, Mar 2012)

-

How Naval Ravikant went to Washington and changed the law (Pando, Nov 2012)

The JOBS Act is a great example of how to create a “Winners Curse”. The JOBS Act has enabled many ultra-low-quality companies to come public via deeply watered-down listing and disclosure requirements. And in an about-face from past regulations, the JOBS Act then allows these dicey companies to use extra-sophisticated advertising methods to target very un-sophisticated investors. As a result, opportunities for mom and pop to invest in low quality companies have become plentiful and easy, simply due to increased supply and visibility.

Meanwhile, separate provisions of the JOBS Act have enabled more promising businesses to avoid coming public until much later in their life. As a result of the JOBS Act, large companies with many de-facto share holders can continue to remain private even as they raise large amounts of capital and issue additional stock options to large number of employees. As a result, by the time these companies (such as Uber and Lyft) do finally choose to come public, the IPO market serves as more of a dumping ground for insiders to exit at lofty valuations, as opposed to being a tool to finance further growth.

As a reminder, the reason Facebook came public at $38 in 2012 was largely because it was forced to do so under prevailing SEC regulations at that time, which were later changed under the JOBS Act.

-

How Goldman Sachs Blew The Facebook IPO (Business Insider, May 2012)

-

Time to Repeal the Rule That Aided Uber’s IPO Flop (Bloomberg, May 2019)

-

Why it’s bad for investors when companies like Uber wait too long to go public (Yahoo Finance, May 2019)

The JOBS Act benefits issuers and intermediaries at the expense of investors. The biggest beneficiary of the JOBS Act was the “fee based financial services industry”. These are the financial intermediaries (banks, brokerages, audit firms, stock exchanges, law firms, etc) whose revenues consist of transaction-based fees and ongoing maintenance fees in the capital markets. As long as there are more transactions (and more publicly listed companies in existence), this overall industry thrives – regardless of whether or not the shares of those companies trade up or down. The second (and more obvious) beneficiary consists of potential issuers (ie. companies) looking to extract money from investors in the capital markets. The JOBS Act made it easier for more companies to sell more securities, to more investors – but with far fewer protections for investors in the past.

(Note: from time to time you may see the occasional article or essay praising the JOBS Act as a glowing success and as providing significant benefits to the market. But if you look closely, you will often find that such commentary has been sponsored or authored directly or indirectly by some fee-based intermediary firm, such as a bank or a law firm).

The Seven Sections of the JOBS Act. The JOBS Act was compiled out of six different bills which had been before Congress in 2011 and 2012. The legislation that was finally passed as a unified JOBS Act is divided into seven sections. The first six Titles bear the names of those original six bills. And the seventh Title requires the SEC to conduct outreach programs, encouraging small businesses, minorities, veterans and women to make use of those first six.

- Title I – Reopening American Capital Markets to Emerging Growth Companies

- Title II – Access to Capital For Job Creators

- Title III – Crowdfunding

- Title IV – Small Company Capital Formation

- Title V – Private Company Flexibility and Growth

- Title VI – Capital Expansion

- Title VII – Outreach On Changes To The Law or Commission

Title I – (reduced disclosure and governance for “emerging growth companies”)

Title I, also known as the “IPO on-ramp,” reduced disclosure rules for up to five years for companies looking to go public which are deemed to be “emerging growth companies”. The criteria for this designation includes companies whose annual gross revenue is less than $1 billion per year and whose first registered equity sale occurred after December 8th, 2011. Emerging growth companies are exempt from certain disclosure rules pertaining to financial statements and executive compensation. They are exempt from the audit of internal controls as required under Section 404(b) of Sarbanes Oxley. They are also not required to comply with new or updated accounting standards. Emerging growth company status ceases when any of the following occur:

- When the company reaches fiscal year gross revenue of $1 billion or more

- The date the SEC deems the company to be a large accelerated filer

- The date that the company has issued over $1 billion in non-convertible debt in the past three years

- Five years after the first registered equity sale

- TOPIC 10 – Emerging Growth Companies (SEC.gov, Jun 2013)

- Emerging Growth Companies (SEC.gov)

- Section 404(b) of Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (AICPA.org,)

- 240.12b-2 Definitions for large accelerated filer (Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, May 2019)

Emerging growth company status permits companies to submit confidential draft registration statements for SEC review prior to these documents becoming public. Any SEC submissions must be made public 21 days prior to a road show.

Title I also made changes related to underwriters and research analysts regarding emerging growth companies. It allows underwriters to “test the waters” for an offering by communicating the company’s intention to raise money with institutional buyers and accredited investors prior to and after the filing of a registration statement. Analysts are allowed to release research reports prior to, during and after an equity raise. This removes prior “quiet period” restrictions preventing analysts from releasing research for 40 days post IPO. Firewalls between bankers, the company and analysts were also removed. These provisions were effective on the signing of the JOBS Act.

-

Quiet Period (Investopedia, Mar 2019)

Title II – (General solicitation and unlimited fundraising from “accredited investors”)

The Securities Act of 1933 requires all sales of any security to be registered with the SEC unless it meets an exemption under Regulation D. Reg D is commonly used for private investments in public equities (PIPEs) and is also used for private debt placements. Capital raises falling under Reg D are exempt from registration. They are often used as a quicker, cheaper route to raising capital compared to traditional registered offerings.

Title II revised Regulation D Rule 506 (safe harbor from registration) by allowing “general solicitation” or advertising of an investment opportunity to the general public without registering with the SEC as long as all investors are accredited investors. Companies can raise an unlimited amount of money from 50 accredited investors. The company must take “reasonable steps” to verify the investors are actually accredited investors by reviewing documents like W-2s, tax returns, bank and brokerage statements, and credit reports. Title II became effective on September 23rd, 2013.

-

Regulation D (Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, May 2019)

-

Regulation D Offerings (SEC.gov)

-

Regulation D (Investopedia, Mar 2019).

-

Rule 506 of Regulation D (SEC.gov)

-

Eliminating Prohibition Against General Solicitation and General Advertising in Rule 506, Rule 144A Offerings (SEC.gov, Sept 2013)

Title III – (“Crowdfunding”)

Title III provides an exemption from securities registration as required under the Securities Act for crowdfunding. It enables companies to issue securities in exchange for money raised via crowdfunding from “internet portals” for both accredited and non-accredited investors. At its initiation companies were allowed to raise up to $1 million annually via crowdfunding, with this cap to be adjusted for inflation every five years.

Non-accredited investors are limited to an annual maximum of either $2,000 or 5% of income if their net worth or annual income are below $100,000. Non-accredited investors with net worth and income both greater than $100,000 can invest up to 10% of the lower amount without exceeding $100,000. There are no limits for accredited investors.

FINRA is responsible for overseeing broker-dealers and funding portals that offer crowdfunding. “Bad actors” (as defined by the SEC) are disqualified from crowdfunding. Regulation Crowdfunding went into effect on May 13th, 2016.

- Spotlight on Crowdfunding (SEC.gov)

- Crowdfunding and the JOBS Act: What Investors Should Know (FINRA.org)

- Regulation Crowdfunding: A Small Entity Compliance Guide for Issuers (SEC.gov, May 2016)

- Regulation Crowdfunding (SEC.gov)

Title IV – (Regulation A+ or the “Mini IPO”)

Title IV of the JOBS Act amended Regulation A and became known as Regulation A+, “Reg A+” or the “mini-IPO,” reg. Although the JOBS Act was passed in 2012, Title IV didn’t become effective until June 19th, 2015.

The original Regulation A had exempted small companies raising up to $5 million from certain registration requirements. Title IV amended Reg A by increasing these exemptions for investments up to $50 million. This opened up the IPO option for the very smallest of companies and requires limited disclosure. Most focus has been on “Tier 2” companies that are allowed to raise up to $50 million annually and are exempt from state regulation. “Tier 1” companies allowed to raise up to $20 million are not exempt from blue sky laws requiring state registration. This additional state burden has made Tier 1 a less popular choice.

- Regulation A+ Takes Effect on June 19, 2015: Making the Grade? (Sidley, Jun 2015)

- Reg A+ Bombshell: $50M Equity Crowdfunding Under Regulation A (Seedinvest)

Advertising of the investment “opportunity” is unrestricted, meaning that things like internet and TV ads are permissible. Both accredited and non-accredited investors can invest, but for Tier 2 non-accredited investors are limited to an annual maximum of either $2,000 or 5% of income if their net worth and annual income are below $100,000. Non-accredited investors with over $100,000 in net worth or income can invest up to 10% of the higher amount.

Companies are required to submit an SEC approved registration statement (Form 1-A) if they decide to go ahead with the sale and are required to submit audited financials, but the number of years of audited financials has been reduced from three to two. Reg A+ companies are required to submit annual reports (Form 1-SA), semi-annual reports (Form 1-K) and current reports (Form 1-U) similar to 8-K’s.

You can read about what the SEC has learned from this process here. In December of 2018 the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act signed into law by President Trump extended Regulation A amendments to all Exchange Act reporting companies.

- Regulation A+: What Do We Know So Far? (SEC.gov, Nov 2016)

- SEC Adopts Final Rules to Allow Exchange Act Reporting Companies to Use Regulation A (SEC.gov, Dec 2018)

- SEC Reporting Companies Can Now Use Regulation A (Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney, Jan 2019)

Title V – (ability for large companies to stay private for longer)

In the past under Section 12(g) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, a company could only have 500 shareholders before having to register with the SEC as a public company. Title V extended that limit to 2,000 shareholders but also specified that registration with the SEC is required if 500 or more shareholders are non-accredited investors. The amendment also changed the definition of “held of record” shareholders to exclude those who receive shares as part of an employee compensation plan. The implication is that companies that were likely to be forced to go public in the past, sometimes purely based on the number of employees provided stock comp, can now stay private much longer. There was no change to the asset limits requiring registration. Companies with less than $10 million in assets are still not required to register regardless of the number of shareholders. The amendments were effective immediately upon the President’s signing but were first adopted by the SEC on May 3rd, 2016.

- 17 CFR 240.12g-1-Registration of securities; exemption from section 12(g) (Cornell Law LII)

- Changes to Exchange Act Registration Requirements to Implement Title V and Title VI of the JOBS Act (SEC.gov, May 2016)

- The JOBS Act, a Year Later – Part 7: Titles V and VI and Concluding Thoughts (Strictly Business, Jun 2013)

Title VI – (Banks and Savings and Loan companies)

Title VI is similar to Title V, but is more specific to banks, bank holding companies, and saving and loan holding companies. Like Title V, Title VI raised the number of shareholders requiring registration from 500 to 2,000, but it differs by not including a limitation on the number of non-accredited investors. This limit also excludes employees who received shares via a stock compensation plan. Also, like Title V if a bank, bank holding company or savings and loan company holds less than $10 million in assets then they do not have to register regardless of the number of shareholders.

- Changes to Exchange Act Registration Requirements to Implement Title V and Title VI of the JOBS Act (SEC.gov)

Title VI also added a separate provision for “deregistration.” If after registering with the SEC, the number of shareholders of a (non-bank) company falls below 300, the company can deregister from the SEC. For banks, bank holding companies and savings and loan holding companies the threshold for deregistering is 1,200 shareholders. Title VI was also effective immediately upon the signing of the JOBS Act.

Title VII (public communication and outreach)

Title VII instructs the SEC to conduct outreach regarding the JOBS Act to small and medium sized businesses, and businesses owned by minorities, veterans, and women.

The rationale for the JOBS Act. In 1997 there were 8,884 companies listed on U.S. exchanges. Since then, the number of listed companies has fallen by over 50%. One obvious culprit for this decline was the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) legislation in 2002 in response to the wave of fraud scandals at companies such as Enron, WorldCom, Waste Management and Tyco. The result of Sarbanes-Oxley was to expand and strengthen corporate governance requirements for public companies while also holding management accountable for their actions and statements. Not surprisingly, the effect of increased regulations and scrutiny meant that many problematic companies would cease to be publicly traded while some new entrants would be less likely to come public in the first place.

- The Death of the IPO (the Atlantic, Nov 2018)

-

Where Have All the Public Companies Gone? (Bloomberg, Apr 2018)

- Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act of 2002 (Investopedia, Apr 2019)

- The 10 Worst Corporate Accounting Scandals of All Time (Accounting Degree Review)

A significant part of the contrived rationale for the JOBS Act rests on the notion that without enough public companies in existence, somehow mom and pop investors will be deprived of adequate opportunities to invest their hard earned money. Therefore, the logic goes, we should make it easier for companies to come public and easier for those companies to advertise to mom and pop investors.

However….a 2018 article in Barron’s observed that the average Reg A+ stock falls 40% in the six months post IPO. That article goes on to evaluate the JOBS Act as follows:

“we were supposed to get new jobs and new industries. Instead, we’ve gotten GoFundMe-style websites hawking penny stocks and professional wrestlers shilling shares on TV….most Reg A+ businesses haven’t gotten beyond the startup phase known as the pipedream.”

- Regulation A+: What Do We Know So Far? (SEC.gov, Nov 2016)

- Microcap Stock: A Guide for Investors (SEC.gov, Sept 2013)

- Updated Investor Bulletin: Regulation A (SEC.gov, May 2019)

- Reg A+ has failed both investors and startups: one founder’s experience (Medium, Apr 2018)

- Longfin’s Over-The-Counter Punch: A $1 Billion Short Squeeze? (IPO Edge, Jun 2018)

- Cryptocurrency Stock Longfin Halted, as SEC Charges Fraud (Barron’s, Apr 2018)

- Most Mini-IPOs Fail the Market Test (Barron’s, Feb 2018)

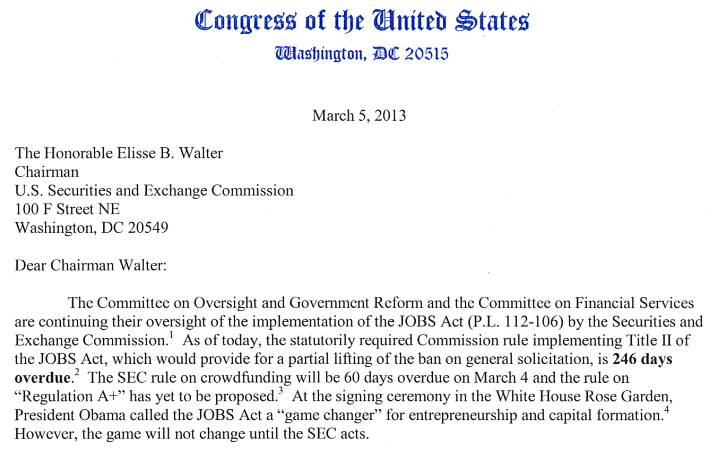

Should you blame the SEC for the JOBS Act ? (Probably not). As shown in several quotes above, current and former SEC staff have seldom been publicly supportive of the JOBS Act. In fact, subsequent to the passage of the Act, the SEC was accused of foot-dragging and doing too little to implement the provisions that had been laid out by Congress. For example, in 2012 Representative Patrick McHenry (R-NC) wrote a letter to the SECs then-chairman Mary Shapiro, accusing her of ignoring the law which had required implementation of Title II which allowed for “general solicitation” (aka “public advertising”) of securities offerings. Later, Rep. McHenry teamed up with Reps Darrell Issa (R-CA), Jim Jordan (R-OH) and Jeb Hensarling (R-TX) by sending another letter to the SEC expressing how dissatisfied they were with the implementation of Titles II, III and IV. Frustrated with early inaction, Rep. McHenry eventually introduced legislation to force the SEC to implement a deadline of October 31, 2013 to enact Title IV related to Reg A+ “mini IPOs.” Title IV was ultimately declared effective by the SEC in June of 2015. Title III Regulation Crowdfunding took a bit longer and became effective in May of 2016.

- SEC Continues to Miss Key Deadline in Implementing JOBS Act, Drawing Ire of Congress (Strictly Business, Aug 2012)

- Eliminating Prohibition Against General Solicitation and General Advertising in Rule 506, Rule 144A Offerings (SEC.gov, Sept 2013)

- H.R. 701 – 113th Congress (Congress.gov, May 2013)

- Regulation A+ Takes Effect on June 19, 2015: Making the Grade? (Sidley, Jun 2015)

- Crowdfunding SEC Final Rule (SEC.gov, May 2016)

- The Benefits and Drawbacks of the JOBS Act (Michigan Business & Entrepreneurial Law Review, Aug 2017)

- What regulation crowdfunding in the JOBS Act means to entrepreneurs and startups (TechCrunch, May 2016)

- Introducing the JOBS Act – or the “Boiler Room Legalization Act” (Nonprofit Quarterly, Mar 2012)

Source: U.S. Congress (Morrison Foerester, Mar 2013)