Summary

- A new proposed ruling by the IRS looks set to disqualify SunCoke’s income for MLP purposes.

- This very subtle change is just now being spotted by more savvy investors who are already dumping the stock while they can.

- Without the MLP benefits, SunCoke could fall by 30-40% more.

- A similar change caused a rapid 30% drop in Westlake Chemical Partners in May.

This article is the opinion of the author. Nothing herein comprises a recommendation to buy or sell any security. The author is short SXC. The author may choose to transact in securities of one or more companies mentioned within this article within the next 72 hours. The author has relied upon publicly available information gathered from sources, which are believed to be reliable and has included links to various sources of information within this article. However, while the author believes these sources to be reliable, the author provides no guarantee either expressly or implied.

Summary

A proposed ruling from the IRS disqualifies for MLP purposes income which is derived from activities which cause “substantial chemical change” in processing or refining. The IRS specifically noted that the new rules are consistent with definitions found within the existing Code.

What the market has missed is that “chemical change” is a defined term with the IRS. Within the existing Code (§1.613-4), the IRS specifically DEFINES “chemical change” by giving the example of “the coking of coal.” As a result, it looks as if SunCoke is set to lose its MLP status based on the proposed regulations. SunCoke has already begun a noticeable selloff. But without MLP status it could easily fall by an additional 30-40%.

Author’s Note: Prior to publication, the author did speak with management at SunCoke. Management felt that because chemicals were not being added in the production of coke that the “chemical change” involved in production was not “substantial.” Management is taking the stance that coking is simply refining and the removal of impurities. Management confirmed that they did not receive a Private Letter Ruling from the IRS for coking, but instead had received only an opinion from their law firm. But even this opinion was only received prior to the new IRS changes. As with Westlake Chemical (NYSE:WLK), SunCoke management is in the process of submitting comments to the IRS.

Section I: Background

On May 6th, 2015, the IRS released new proposed regulations which substantially change the rules relating to qualifying income for MLPs from the processing, refining and transportation of minerals or natural resources which allows a business to be treated as a partnership for U.S. federal tax purposes.

The full text of the proposed changes was later posted as a bulletin to the IRS website on May 26th and can be found here.

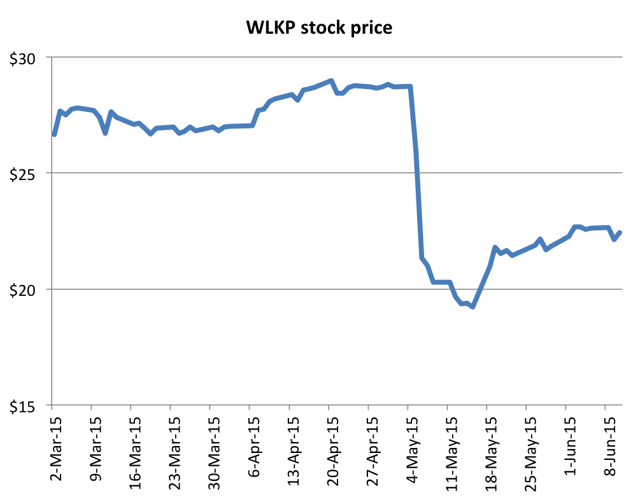

The proposed changes had an immediate impact on Westlake Chemical Partners LP (NYSE:WLKP). Within 3 days, the shares had fallen by as much as 30%. This was the case even though West Lake had previously obtained a Private Letter Ruling (“PLR”) to the effect that the production, transportation, storage and marketing of ethylene and its co-products constitutes “qualifying income” within the meaning of the Code.

According to the new proposed regulations, because Westlake had previously obtained the PLR, its existing activities would continue to be treated as qualifying income for 10 years. And yet the shares fell by as much as 30% before stabilizing. The shares did subsequently bounce slightly once investors grasped the 10-year grandfather period.

Section II: Changes affecting SunCoke Energy

The situation is much worse for SunCoke Energy Inc. (NYSE:SXC) and its LP SunCoke Energy Partners LP (NYSE:SXCP). A few of the more savvy investors must have already spotted this, explaining the recent selloff in SunCoke.

Shares could easily fall by 30-40% once the implications of the new regulations are fully grasped by investors as a whole.

SunCoke is engaged in the processing of coal into coke for steel making. What the larger market has entirely missed is that the new regulations look to outright prohibit coking activities from being treated as qualifying income.

In addition, because SunCoke had not received a PLR from the IRS for coke production, it would not get the 10-year extension for existing activities, as did Westlake. I did confirm with management that they did not receive a PLR from the IRS.

A good overview of the general rule changes is summarized by Chadbourne and Park:

The proposed regulations treat income as qualifying income only if it is from engaging directly in “exploration, development, mining or production, processing or refining, transportation or marketing” of minerals or natural resources or from providing a limited class of services to companies that are directly engaged in such activities.

A more detailed read of the proposed rule-making reveals the problem which is unique to SunCoke.

We can see clearly from item 1.D of the new proposed rule-making that the IRS states specifically that:

processing or refining does not include activities that cause a substantial physical or chemical change in a mineral or natural resource, or that transform the extracted mineral or natural resource into new or different mineral products, including manufactured products. The Treasury Department and the IRS believe that this rule is consistent with definitions found elsewhere in the Code and regulations. See, for example, § 1.613-4(G)(5).

(See appendix I for full text of Item D)

Although it is more difficult to find, we can also see from the US Federal Tax Code (§ 1.613-4) that the term “chemical change” is well defined. In fact, the tax code actually uses coking as a specific example to outright DEFINE an activity that constitutes “effecting a chemical change.”

This is what the overall market has missed. IRS Code § 1.613-4 states very clearly and specifically that:

The term treatment effecting a chemical change refers to processes which transform or modify the chemical composition of a crude mineral, as, for example, the coking of coal.

(See Appendix II for full text of this definition section)

KEY POINT: The recent proposed rule change made it clear that “this rule is consistent with definitions found elsewhere in the Code.” And we can see from the definitions provided by the IRS that there is just a single example to define “chemical change.” That single example is “the coking of coal.”

Section III: The chemical change in coking

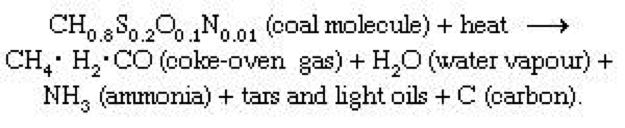

Any variety of sources can be used to see the exact chemical change involved in coking. For example, Britannica.com includes the following diagram.

Additional sources can clarify the above reaction diagram as:

When heated to high temperatures, in the absence of air, the complex organic molecules break down to yield gases, together with liquid and solid organic compounds of lower molecular weight and a relatively non-volatile carbonaceous residue ( coke ). Coke, then, is the residue from the destructive distillation of coal.

Some of this should be viewed as common sense. The diagram above shows the before and after of coke vs. coal. Some of the byproducts such as the gases and the ammonia (released during the chemical change) can even be sold off separately. Coke is a different compound than the original coal. Due to the chemical changes, coke is also much lighter than coal, which is a physical change.

Section IV: Impact on SunCoke

With SunCoke, the most compelling short opportunity is with the GP, although the LP should be expected to fall substantially as well.

At current prices, the driving value proposition in SunCoke Energy (the GP) is the prospect for increased dropdowns going forward. This has been clearly stated in a series of 13Ds by Jet Capital and was amplified recently in an article on Seeking Alpha, “Jet Capital on Coking Coal.”

Without the benefit of the MLP structure, the business is simply a money losing coke producer which is trading at a highly inflated EBITDA multiple.

SunCoke currently trades with an enterprise value of around $1.7 billion vs. adjusted EBITDA of $218 million (consensus for 2015). This is an EBITDA multiple of around 8x. But without the benefit of the MLP structure this should drop to around 6x or below. This could see at least $400 million shaved off of the market cap in short order.

More importantly, the current base of holders is heavily skewed towards hedge funds who are holding in anticipation of the future dropdown benefits. They certainly aren’t looking to be long-term holders of a money losing coke producer.

It seems clear from the continued weakness in the share price that some of the savvier holders of SunCoke have already started to figure this out.

But there is likely to be around 30-40% more downside once the laggards figure out the implications of the upcoming changes.

Appendix I – text from IRS bulletin 2015-21 Section 1D

The full text of this bulletin can be found here. The relevant section is Section D.

D. Processing or Refining.

Because processing and refining activities vary with respect to different minerals or natural resources, these proposed regulations provide industry specific rules (described herein) for when an activity qualifies as processing or refining. In general, however, these proposed regulations provide that an activity is processing or refining if it is done to purify, separate, or eliminate impurities. These proposed regulations further require that, for an activity to be treated as processing or refining, the partnership’s position that an activity is processing or refining for purposes of section 7704 must be consistent with the partnership’s designation of an appropriate Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) class life for assets used in the activity in accordance with Rev. Rul. 87-56 (1987-2 CB 27) (for example, MACRS asset class 13.3 for petroleum refining facilities). In addition, except as specifically provided otherwise, processing or refining does not include activities that cause a substantial physical or chemical change in a mineral or natural resource, or that transform the extracted mineral or natural resource into new or different mineral products, including manufactured products. The Treasury Department and the IRS believe that this rule is consistent with definitions found elsewhere in the Code and regulations. See, for example, § 1.613-4(5).

Appendix II – text from US Tax Code §1.613-4 section (6)

The full text of the definitions section can be found here.

See item (vii) for the definition of “chemical change”

(6) Definitions. As used in section 613(c)(5) and this section:

(i) The term calcining refers to processes used to expel the volatile portions of a mineral by the application of heat, as, for example, the burning of carbonate rock to produce lime, the heating of gypsum to produce calcined gypsum or plaster of Paris, or the heating of clays to reduce water of crystallization.

(ii) The term thermal smelting refers to processes which reduce, separate, or remove impurities from ores or minerals by the application of heat, as, for example, the furnacing of copper concentrates, the heating of iron ores, concentrates, or pellets in a blast furnace to produce pig iron, or the heating of iron ores or concentrates in a direct reduction kiln to produce a feed for direct conversion into steel.

(iii) The term refining refers to processes (other than mining processes designated in section 613(c)(4) or this section) used to eliminate impurities or foreign matter from smelted or partially processed metallic and nonmetallic ores and minerals, as, for example, the refining of blister copper. In general, a refining process is designed to achieve a high degree of purity by removing relatively small amounts of impurities or foreign matter from smelted or partially processed ores or minerals.

(iv) The term polishing refers to processes used to smooth the surface of minerals, as, for example, sawing applied to finish rough cut blocks of stone, sand finishing, buffing, or otherwise smoothing blocks of stone.

(v) The term fine pulverization refers to any grinding or other size reduction process applied to reduce the normal topsize of a mineral product to less than .0331 inches, which is the size opening in a No. 20 Screen (U.S. Standard Sieve Series). A mineral product will be considered to have a normal topsize of .0331 inches if at least 98 percent of the product will pass through a No. 20 Screen (U.S. Standard Sieve Series), provided that at least 5 percent of the product is retained on a No. 45 Screen (U.S. Standard Sieve Series). Compliance with the normal topsize test may also be demonstrated by other tests which are shown to be reasonable in the circumstances. The normal topsize test shall be applied to the product of the operation of each separate and distinct piece of size reduction equipment utilized (such as a roller mill), rather than to the final products for sale. Fine pulverization includes the repeated recirculation of material through crushing or grinding equipment to accomplish fine pulverization. Separating or screening the product of a fine pulverization process (including separation by air or water flotation) shall be treated as a nonmining process.

(vi) The term blending with other materials refers to processes used to blend different kinds of minerals with one another, as, for example, blending iodine with common salt for the purpose of producing iodized table salt.

(vii) The term treatment effecting a chemical change refers to processes which transform or modify the chemical composition of a crude mineral, as, for example, the coking of coal.

The term does not include the use of chemicals to clean the surface of mineral particles provided that such cleaning does not make any change in the physical or chemical structure of the mineral particles.

(viii) The term thermal action refers to processes which involve the application of artificial heat to ores or minerals, such as, for example, the burning of bricks, the coking of coal, the expansion or popping of perlite, the exfoliation of vermiculite, the heat treatment of garnet, and the heating of shale, clay, or slate to produce lightweight aggregates. The term does not include drying to remove free water.